2.2 ASH Service Area

The new ASH facility is part of a system-wide initiative led by HHSC to renovate or build new hospitals throughout Texas. Included in this initiative are facilities at Kerrville, Rusk, San Antonio, Austin, Houston and Dallas. The new Houston hospital, the John S. Dunn Behavioral Sciences Center, opened in April 2022 resulting in redefining the ASH service area. The addition of the Dunn Center provided 264 new beds, with 196 of those beds dedicated to the State Hospital System.

At the start of the ASH Redesign, its catchment area comprised 38 counties for adults. However, with the Dunn Center, a new service area was established for the Houston hospital, relieving ASH from several southeastern counties in which people could be better served by a Harris County based facility. The ASH service area reduced from 38 to 26 counties for adult services with a corresponding 37% decrease in population (~1.5M adults) in the new service area. This change in service area involved reassigning 8 rural counties and 4 urban counties to the Dunn Center. The June 2021 US Census estimated the populations in the new ASH service area to be 2.6M adults. See Figure 1 for the redefined ASH service area.

Figure 1: Updated ASH Service Area

With the addition of the Dunn Center, people in need of care from southeast Texas will no longer have to drive past Houston all the way to Austin for services. This change will improve access to the regional population as well as decrease hours spent transporting people in ambulances or by law enforcement. A service area has not been defined for the new Dallas state hospital, but will add inpatient state beds, even if it does not impact the ASH service area directly.

“The ASH service area reduced from 38 to 26 counties for adult services with a corresponding 37% decrease in population (~1.5M adults) in the new service area.”

In Phase I of the ASH Redesign, we examined the capacity of private inpatient psychiatric hospitals throughout the ASH service area. The original ASH service area included 26 private psychiatric hospitals and a total of 995 beds. Since the first report there have been closures (6) and openings (3) of 8 private hospitals inpatient psychiatric services. Coupled with the opening of the Dunn Center, the new ASH service area now has 16 private psychiatric hospitals with an estimated range of 700-920 inpatient psychiatric beds. The number of psychiatric inpatient beds has fluctuated throughout Phase III, often tied to the fluctuation of staffing levels limiting access to beds; therefore, we will use a conservative count of 700 private inpatient beds. This fluctuation also impacts ASH, as the key focus of the work group’s recommendations is to improve hiring and retaining mental health workers. With these considerations in mind, we examined the current psychiatric bed need for the ASH Service Area. A recent report by Hudson, et al (2021) suggests that Texas needs ~35 inpatient beds per 100,000 population. By applying a similar review to the new ASH service area as Hudson et al, there is a need of 923 inpatient psychiatric beds. If all private inpatient (700 beds) and the new ASH (240 beds) operate fully staffed and at capacity, the service area will have approximately 940 inpatient psychiatric beds, thereby meeting demand. However, the ability to meet demand with these hospital beds requires that the hospitals are used only to provide hospital level services, with other clinical needs being met in more appropriate settings. The ASH service area then has enough psychiatric beds to support the population in the service area if there exists an adequate care continuum. This would be dependent on using hospitals as intended and expand efficiencies in the continuum of care will best serve Central Texan’s mental health needs.

The improvements in hospital facilities established by HHSC and the Legislative investment alone will not solve the current mental health crisis the State is experiencing in long wait times for a state psychiatric bed. To alleviate this crisis, all the new hospitals must be operated at capacity and the continuum of mental health care must be expanded to assist with the waitlists of people waiting in jail with critical needs for intensive mental health care. Without expansion of care across the continuum, system, and practice changes in other systems (e.g., counties, law enforcement, jails, courts,) occur, it will continue to produce the results it is currently attaining, failing to address the needs of many of Central Texan’s citizens.

Admissions and Discharges

The Phase II report averaged 95 people waiting for an ASH Bed. There are compounding issues that increased the ASH waitlist. In October 2022, there are almost 400 people waiting for a bed in ASH and there are roughly 2,500 people waiting statewide. Within the last few years, several significant events have increased the number of persons and the length of time waiting for a bed at ASH.

The COVID-19 pandemic required the state hospitals to adjust the number of people to a room to decrease the potential spread of the virus. The current building is not designed for quarantining. Notably, the new ASH is designed for single occupancy rooms, so would have been better equipped to meet the demands of the pandemic.

The “great resignation” seen across the US during and following the pandemic has most significantly impacted the healthcare system. ASH, like most of the healthcare system, has lost several employees that have not yet been replaced. From April of 2021 to August of 2022, the ASH fill rate for psychiatric nurses and psychiatric nursing assistants has steadily declined from 86% to 63%.

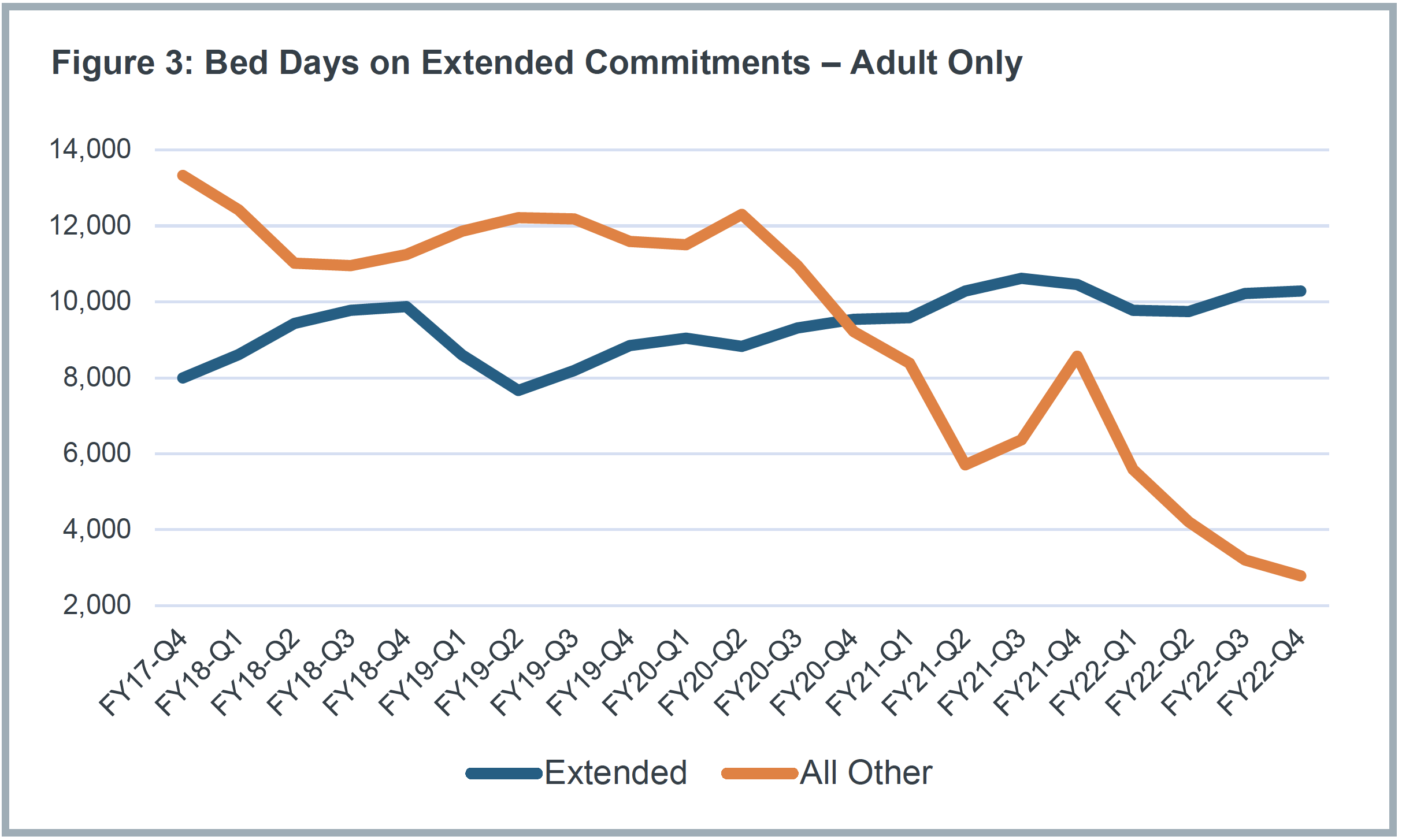

During the past few years, courts have increasingly filed competency restoration commitments for people found incompetent to stand trial, dominating the use of state hospitals including ASH. Figure 2 represents the increase in felony adults to the hospital and extended commitments (figure 3).Combined, the increased felony admits, and extended commitments create a bottleneck and slow the function of the state hospital beds. Rather than turning over for new people to receive care, the bed remains with a single person increasing the waitlist. Additionally, 54% of the adult patients at ASH are on an extended forensic commitment. These are most often patients deemed unlikely to restore competency or people not guilty by reason of insanity (NGRI)commitments. These extended commitments remain in State Hospital beds, thus limiting capacity for new admissions.

The lack of alternative appropriate clinical (and competency restoration)placements has led to the state hospital serving as the default for a wide range of clinical and competency restoration needs. With better infrastructure, and collaborative legal and clinical diversion alternatives, much of this work could be managed in the community on an outpatient basis. People need to be instate hospitals, including ASH, only when they need acute and subacute clinical care.

As the waitlist increased throughout the years, admissions to ASH slowed (Figure 4). The effect of the increased felony admits and extended commitments, results in Figure 4, the slowed admissions. The slowing of discharges was also impacted by COVID-19, as many community supports paused their admissions to slow the spread of the virus in their facilities. As mentioned throughout all phases of the ASH Redesign there are very limited community options to discharge some of the individuals receiving care at ASH. At times, ASH becomes a long-term residential care facility, diminishing its capacity as an acute or subacute care hospital due to the absence of more step-down and discharge options for individuals in the system.

The need for all levels of mental health care is greater than the service area can support. This need leads to excessive and unnecessary reliance on state hospitals, including ASH, due to lack of alternatives. Changes both in preventative outpatient mental health care prior to admission to and re-entry into the community mental health care from ASH are needed to address the community’s increase need. Moreover, these mental health needs are not new, and unfortunately the pandemic has both highlighted and increased the demand. In March 2022, World Health Organization stated the pandemic increased the prevalence of anxiety and depression by 25% worldwide. As the need for mental health care has increased, local and state efforts will need to grow with the demand to keep people healthy.

HHSC Behavioral Health Services Division Efforts and Engagements

As mentioned previously in this section, HHSC’s Health and Specialty Care System has several new hospital or hospital renovation projects underway to improve their inpatient psychiatric hospital facilities. Parallel with this effort, the Behavioral Health Services (BHS) division oversees community-based programs, services, and policy to increase access to community-based mental health care and includes Mental Health and Substance Use Programs (MHSUP), the Office of Mental Health Coordination (OMHC), the Office of Forensic Coordination (OFC), and Rural Mental Health (RMH). MHSUP has expanded access to crisis, diversion, outpatient and jail-based competency restoration, and outpatient mental health services and oversees the Step-Down Housing Pilot which provides step-down housing for expansion of community-based and outpatient services in the continuum of care. OMHC leads the Statewide Behavioral Coordinating Council, which recently released the FY2022-2026 Texas Statewide Behavioral Health Strategic Plan including the Texas Strategic Plan for Diversion, Community Integration and Forensic Services. All Texas Access, led by Rural Mental Health, focuses on increasing access to mental health services in rural Texas communities. The Office of Forensic Coordination carries out the statutory responsibilities of statewide oversight and coordination of forensic services and promotes statewide initiatives to address drivers of the forensic waitlist and incarceration of people with mental illness and substance use disorders. These goals are accomplished by leading statewide and cross-agency initiatives that improve coordination and collaboration among state and local leaders. The OFC liaisons with the Joint Committee on Access & Forensic Services, an HHSC advisory board, subject matter expertise to the full committee, as well as to the Access and Data Subcommittees. Another key initiative, Eliminate the Wait, is a statewide campaign led by the OFC in partnership with the Judicial Commission on Mental Health, Texas Sheriff’s Association, Texas Police Chiefs Association, and the Texas Council for Community Centers that focuses on eliminating the wait for inpatient competency restoration services through education and training for county justice and behavioral health stakeholders.

The ASH Redesign team is engaged with the Behavioral Health Services division to support Texans in need of brain health care in the community. As collaborations have grown throughout the projects and teams, efforts are underway creating a more efficient and effective mental health system by working towards decreasing the waitlist, increasing access to a variety of services, and continuing to meet and discuss innovative solutions is underway.

Key Points – ASH Service Area:

• ASH’s new service area for adults decreases from 38 to 26 counties.

• Waitlists for inpatient psychiatric care increases while admissions decreased, caused by compounding issues of COVID-19 and staff shortages.

• Efforts through HHSC and ASH Redesign continue to aim for efficient and effective care for people needing mental health care.